Geoffrey Hawtin and Cary Fowler

United Kingdom/Canada and United States

Dr. Geoffrey Hawtin and Dr. Cary Fowler will receive the 2024 World Food Prize for their extraordinary leadership in preserving and protecting the world’s heritage of crop biodiversity and mobilizing this critical resource to defend against threats to global food security. Over the last 50 years, their combined efforts as researchers, policy advisors, thought leaders and advocates have succeeded in engaging governments, scientists, farmers and civil society towards the conservation of over 6,000 species of crops and culturally important plants.

Links:

Press Advisory | Press Release | Photos

Laureate Story | Social Media Kit

2024 Laureate Announcement

2024 Laureate Award Ceremony - Coming Soon

Laureate Video - Coming Soon

FROM SEEDS TO SECURITY

Hawtin and Fowler are highly regarded as the world’s foremost experts on global crop biodiversity and genetic resources, which are essential to long-term global food security in the face of climate change, pandemics, conflicts and other existential threats. They have been principally involved in the most important innovations in plant genetic resources throughout their careers, especially in operating and funding crop genebanks all over the world.

Genebanks are crucial resources for scientists who develop improved varieties of the world’s most important food crops. The biological material in about 7.4 million samples held in more than 1,750 genebanks around the world contains beneficial traits with the potential to improve crops’ climate resilience, disease resistance, nutritional value and tolerance to high salinity. This is increasingly valuable as these preserved varieties are rapidly disappearing from farmers’ fields. It is estimated that we have already lost more than 90 percent of the biodiversity of many of the crop species that are relied on across the world.

“It’s genetic diversity that underpins agriculture today. If we didn’t have a lot of different varieties, if we didn’t have a lot of different crops, each one adapted to a different niche around the world, we wouldn’t have agriculture. So it’s also this genetic diversity that is underpinning the agriculture of the future,” Hawtin said.

“It’s genetic diversity that underpins agriculture today. If we didn’t have a lot of different varieties, if we didn’t have a lot of different crops, each one adapted to a different niche around the world, we wouldn’t have agriculture. So it’s also this genetic diversity that is underpinning the agriculture of the future,” Hawtin said.

While serving as Director General and Senior Advisor, respectively, at the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute in the 1990s, Hawtin and Fowler led the CGIAR delegation in the years-long United Nations (UN) negotiations around the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture (Plant Treaty). Though the Convention on Biological Diversity, which came into effect in 1993, promoted sharing access to biological materials through bilateral agreements between nations, this effectively stymied the sharing of agricultural genetic diversity. The extensive international movement of crops over centuries has made nations highly interdependent for genetic resources. For example, one variety of maize may have parental lines originating in 20 different countries and be grown by farmers in many more. This makes it practically impossible to negotiate access on a bilateral basis.

Recognizing this, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) launched negotiations for the Plant Treaty to address the issue of sharing crop genetic resources. The Laureates’ technical and policy input to the Plant Treaty resulted in formalizing the diversity of 64 food and forage crops housed in genebanks as international public goods, to be shared with a multilateral access system. This ensured the protection of plant genetic resources for food and agriculture and facilitated the movement of these resources to those who need them throughout 149 countries that signed the agreement. Since 2012, international genebanks have distributed close to one million samples to users in more than 120 countries under the Plant Treaty.

The Plant Treaty recognized the importance of a stable source of funding as an essential element for the protection of these collections. To meet this need, Hawtin founded the Global Crop Diversity Trust (Crop Trust), raising tens of millions of dollars for a non-wasting endowment fund that now provides funding in perpetuity for genebanks the world over as well as projects aimed at conserving crop diversity. When Fowler took over leadership of the Crop Trust from Hawtin in 2005, he further expanded funding and broadened its mission with projects aimed at rescuing at-risk repositories and collecting crop wild relatives.

“We’re trying to teach the world how to save itself. We’re really in a race against time. We need to mobilize before it’s too late,” said Fowler. “We’re going to pay a price if we don’t do the smart thing and help agriculture adapt.”

A SEED VAULT IN SVALBARD

Both Fowler and Hawtin were instrumental in establishing the highly acclaimed Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway, built for the purpose of serving as the world’s long-term secure backup repository for crop diversity. Fowler chaired the Norwegian government’s committee, of which Hawtin was also a member, that collectively assessed the feasibility of the proposed Vault. Fowler continued to lead the negotiations for opening the Vault, helping to break through deadlocks in international politics and secure support from national and international genebanks. He served nine years as the Chair of the Vault’s International Advisory Council. Meanwhile, Hawtin developed technical, management and policy specifications for the Vault which were used by the Norwegian government in its construction and operation.

In its 15 years of operation, the Vault now safeguards 1.25 million accessions of crops, their wild relatives and other culturally important plants from over 6,000 species from nearly every country in the world. This collection represents the world’s largest and most diverse library of crop biodiversity. Deposits at the Vault have been made by more than 100 institutions, civil society organizations and indigenous communities.

“The seeds that are in there represent the history of agriculture. So what they really represent is the experiences that our crops have had over twelve to fifteen thousand years,” said Fowler. “We’ve co-evolved with each other. We both depend on each other, and we both reflect each other. Our agricultural system goes back hundreds of human generations. So all of our ancestors have had a role in conserving this diversity and handing it forward to us. We just have to hand it off to the next generation. That’s doable.”

The Vault has already proven its value by preserving backups of the ICARDA genebank, which were crucial in rebuilding the collection after it was destroyed in the Syrian civil war. The restored samples even included seeds collected by Hawtin and his team decades before.

The Vault has already proven its value by preserving backups of the ICARDA genebank, which were crucial in rebuilding the collection after it was destroyed in the Syrian civil war. The restored samples even included seeds collected by Hawtin and his team decades before.

“With an annual running cost of about USD 300,000, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault must rank among the world’s best insurance policies,” said Hawtin.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is a crowning achievement in the careers of Fowler and Hawtin, as it was made possible by decades of their contributions to crop biodiversity conservation and mobilization. Indeed, the Vault would never have opened without their work on the Plant Treaty and the Crop Trust, under which the Vault is able to operate internationally.

More than anyone else, Hawtin and Fowler have together shaped the global system we now have for protecting, sharing and utilizing crop biodiversity for the benefit of humanity.

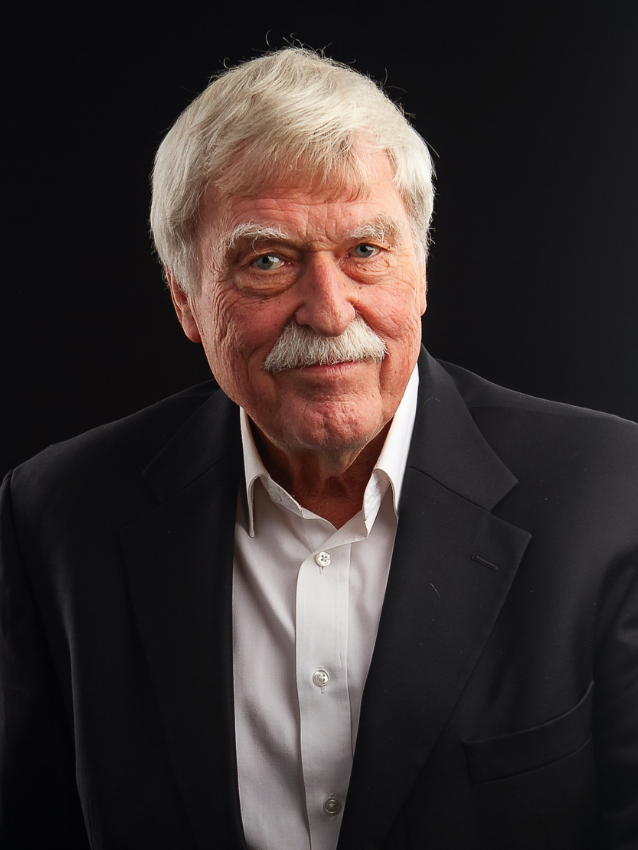

DR. GEOFFREY HAWTIN

Though he grew up in north London, England, Geoffrey Hawtin spent many of his summers in the country, working on a farm. Though he was considered a “townie” in the countryside, his classmates in the city called him “farmer Hawtin” after he told his headmaster he wanted to be a farmer when he grew up. His parents, both geography teachers, instilled in him a love of traveling and learning about the world.

Though he grew up in north London, England, Geoffrey Hawtin spent many of his summers in the country, working on a farm. Though he was considered a “townie” in the countryside, his classmates in the city called him “farmer Hawtin” after he told his headmaster he wanted to be a farmer when he grew up. His parents, both geography teachers, instilled in him a love of traveling and learning about the world.

While he was studying at Cambridge University, his professor Alice Evans encouraged him to focus his studies in plant genetics and go to Uganda to do his doctorate research at Makerere University. While Hawtin was in Uganda, a coup d’état saw Idi Amin taking power. Many of the foreign university staff departed the country, but Hawtin stayed to finish his research—and took over teaching the undergraduate genetics and agronomy courses to fill the gap in faculty. As it turned out, the Ugandan coup was not to be the last conflict that would put Hawtin to the test.

After graduating, Hawtin began working with the Arid Lands Agricultural Development (ALAD) Program, which later became part of the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA). He led teams in the field in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and Turkey to collect local varieties of lentils and legumes. They had built a substantial collection of seeds—around 20,000 accessions of chickpeas, fava beans and lentils—when civil war erupted in Lebanon. This posed a substantial threat to the materials in the genebank, which, if destroyed, could never be replaced.

One night, Hawtin was kept awake by the shelling that was happening just over the house in which he was sheltering. The next day, he and his team loaded the collections into two pickup trucks and drove 25 kilometers down a potholed road lined with burned-out vehicles, hoping that they would not hit a landmine. When they got to the Syrian border, they were turned away and had to drive all the way back. They made this journey twice more before they were finally allowed to enter Syria and get themselves and the seeds to safety.

Hawtin worked in the Middle East for twelve years, also weathering the 1982 Lebanon War, when the Syrian Army used the ICARDA research station as their base.

Hawtin worked in the Middle East for twelve years, also weathering the 1982 Lebanon War, when the Syrian Army used the ICARDA research station as their base.

“With gunfire in the distance, I asked the commander to please be careful and try to avoid running over our research plots with their armored vehicles when they left,” Hawtin recalls. “He pointed to a tree on the hillside a mile or so away and said, ‘If we withdraw before the Israelis get to that tree, we will be careful. But once they reach the tree, all bets are off!’”

Hawtin then got the opportunity to serve as Director of the Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Sciences Division of Canada’s International Development Research Center, where he oversaw some 400 projects in more than 70 different countries.

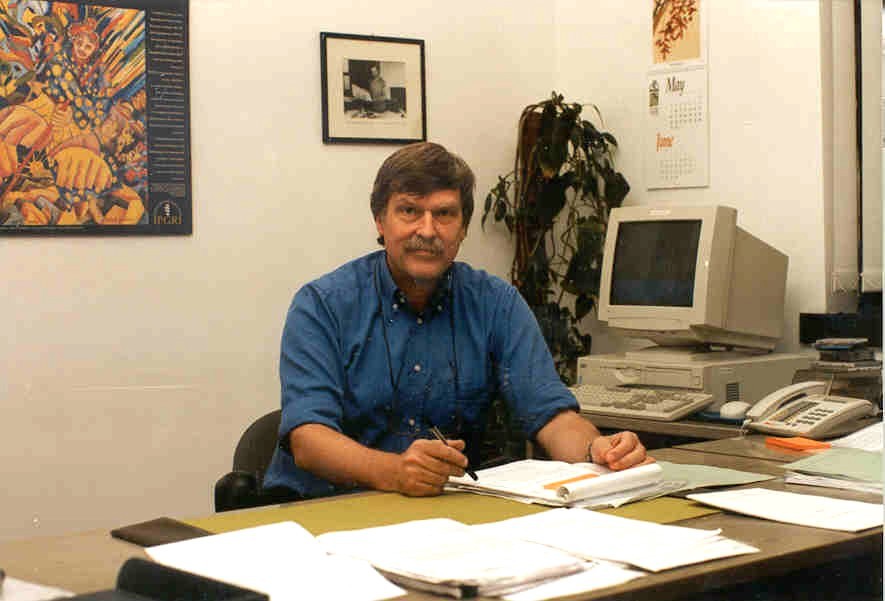

In 1991, Hawtin accepted the position of Director of the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR) housed at the FAO. Under his leadership, the IBPGR was transformed from a moderate-sized program that focused almost exclusively on genebank conservation to an independent, multidimensional CGIAR center, becoming the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI—later renamed Bioversity International). He tripled the budget and led the development of diverse international research programs in areas including conservation of crop wild relatives, forest genetic resources, indigenous knowledge and ethical and policy issues. He penned the first institutional strategy for the center, “Diversity for Development”.

“Diversity underpins success in all areas of life; it should be appreciated, cherished and safeguarded,” Hawtin said.

After a series of turbulent meetings with various nongovernmental organizations during the final negotiation of the Convention on Biological Diversity in Kenya, Hawtin realized that something must be done to assure the public that collections in genebanks would always remain in the public domain. He convinced the CGIAR centers to sign an agreement with the FAO placing their germplasm collections in trust for the benefit of the world community, a move which fostered good faith and cooperation among the CGIAR, nongovernmental organizations and indigenous communities. Along with the Plant Treaty, this opened the way politically for the establishment of the Crop Trust and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

After a series of turbulent meetings with various nongovernmental organizations during the final negotiation of the Convention on Biological Diversity in Kenya, Hawtin realized that something must be done to assure the public that collections in genebanks would always remain in the public domain. He convinced the CGIAR centers to sign an agreement with the FAO placing their germplasm collections in trust for the benefit of the world community, a move which fostered good faith and cooperation among the CGIAR, nongovernmental organizations and indigenous communities. Along with the Plant Treaty, this opened the way politically for the establishment of the Crop Trust and the Svalbard Global Seed Vault.

One day, Hawtin received a request to IPGRI from an African national genebank for funding. They needed just $5,000 for electricity to keep their seed storage coolers running. Without electricity, 50 years of irreplaceable collections could be lost overnight. Hawtin realized then that reliable, sustainable funding for genebanks was truly what was needed by many genebanks in order to avert disaster. This triggered his idea for what would become the Crop Trust and its endowment fund for the conservation of these collections.

As a member of the Executive Board of the Crop Trust, Hawtin continues the mission of the organization he started to conserve crop diversity and make it available for all to use, forever.

DR. CARY FOWLER

“I remember in the summertimes when I would be on the family farm, there was always a sense that you had to look after your neighbors. There was a sense of community, and that you had a responsibility back to the greater society,” Fowler said.

Cary Fowler grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, but spent his summers visiting his grandmother’s small farm. Though his grandmother wanted him to take over the farm one day, Fowler wasn’t so sure at the time that it was for him. He was very interested in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, even attending the last speech given by Martin Luther King Jr. the day before his death. Fowler avidly debated these issues on his school’s debate team, and he thought that he would like to do something in politics or law, like his father, a judge for 22 years. He pursued social studies throughout earning his undergraduate degree at Rhodes College and Simon Fraser University.

Cary Fowler grew up in Memphis, Tennessee, but spent his summers visiting his grandmother’s small farm. Though his grandmother wanted him to take over the farm one day, Fowler wasn’t so sure at the time that it was for him. He was very interested in the civil rights movement of the 1960s, even attending the last speech given by Martin Luther King Jr. the day before his death. Fowler avidly debated these issues on his school’s debate team, and he thought that he would like to do something in politics or law, like his father, a judge for 22 years. He pursued social studies throughout earning his undergraduate degree at Rhodes College and Simon Fraser University.

It wasn’t until he began doing research for the Southern Exposure journal on the disappearance of family farms and for author Frances Moore Lappé on global food policy that he began to see how his two greatest interests—agriculture and social justice—fit together. The works of botanist Jack Harlan opened his eyes to the unfolding disaster that was the loss of crop diversity. This convinced Fowler that the most essential thing for him to do was to conserve crop diversity for humankind, which set him on his career path. He soon became involved in promoting international action at the FAO to secure farmers’ rights to the seeds they had stewarded for generations. He and his colleague Pat Mooney first proposed an international treaty on crop diversity and the idea of an international genebank there in 1979.

Fowler wrote the first funding proposals for the Livestock Conservancy and for Seed Savers Exchange in Decorah, Iowa, while he was Program Director at the National Sharecroppers Fund in the 1970s. He later joined the board of Seed Savers, where he met his wife, author Amy Goldman, who shared his passion for conserving crop varieties.

During this time, Fowler and Hawtin also worked closely with Dr. M.S. Swaminathan on the Keystone International Dialogue Series on Plant Genetic Resources, which brought together stakeholders from CGIAR, the UN, genebanks, nongovernmental organizations and seed and biotechnology companies to reduce conflicts over and find common ground for the security and sustainable use of crop diversity. For Fowler, as it was for many, the Dialogues were a turning point that showed him the value of negotiating and working together with diverse actors for a solution that will benefit all.

In 1990, Fowler moved to Scandinavia to serve as an Associate Professor at the Norwegian College of Agriculture, while he was completing his doctorate at Uppsala University in Sweden. Soon though, he was approached by the FAO for a very different opportunity.

In 1990, Fowler moved to Scandinavia to serve as an Associate Professor at the Norwegian College of Agriculture, while he was completing his doctorate at Uppsala University in Sweden. Soon though, he was approached by the FAO for a very different opportunity.

As Head of the Secretariat of FAO’s International Conference and Program for Plant Genetic Resources in the ‘90s, Fowler prepared the UN’s first assessment of the world’s plant genetic resources. He also led the research, drafting and participatory negotiation process through a dozen regional meetings that culminated in 150 countries adopting a Global Plan of Action for conserving and using these resources for agriculture. This was a first step toward a worldwide genebank management plan, supplementing the negotiations for the Plant Treaty.

In 2003, Fowler wrote a letter to the Norwegian government asking them to consider establishing an international seed vault in Svalbard. When he met with the Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs to discuss the idea, he got straight to the point.

“At one point he said, ‘Let me get this straight. Are you telling me these seeds that you want to conserve are really one of the most valuable natural resources on earth?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ And then he said, ‘And are you also telling me that Svalbard is the best place on Earth to do that?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He said, ‘Then, how can we say no?’”

While a member of the Board of Trustees of CIMMYT, Fowler made a habit of eating breakfast before board meetings with Dr. Norman Borlaug, as they were both early risers. He remembers Dr. Borlaug’s enthusiasm for speaking with students and his boundless energy for making progress in agriculture. Even at age 87, when Fowler hosted him at the Norwegian College of Agriculture for the centennial celebration of the Nobel Peace Prize, Borlaug’s 1.5-hour lecture was looking forward to the future of food. But Fowler also remembers Borlaug’s prediction that the Green Revolution had only bought them a few decades of time to make the next leap forward in agriculture.

In Fowler’s current position as U.S. Special Envoy for Global Food Security, he launched and leads the initiative for a Vision for Adapted Crops and Soils, focusing on the diversity of nutritious, climate-adapted, traditional crops for improved food and nutrition security. The movement pulls together everything Fowler has learned through his career, marrying under-invested but promising crops with soil health, nutrition, climate adaptation, gender equity, computer modeling and more for a comprehensive approach to long-term sustainable agriculture systems. It is a movement that he has drawn in the support of many of his now fellow World Food Prize Laureates, and one he believes Dr. Borlaug could get behind.

In Fowler’s current position as U.S. Special Envoy for Global Food Security, he launched and leads the initiative for a Vision for Adapted Crops and Soils, focusing on the diversity of nutritious, climate-adapted, traditional crops for improved food and nutrition security. The movement pulls together everything Fowler has learned through his career, marrying under-invested but promising crops with soil health, nutrition, climate adaptation, gender equity, computer modeling and more for a comprehensive approach to long-term sustainable agriculture systems. It is a movement that he has drawn in the support of many of his now fellow World Food Prize Laureates, and one he believes Dr. Borlaug could get behind.