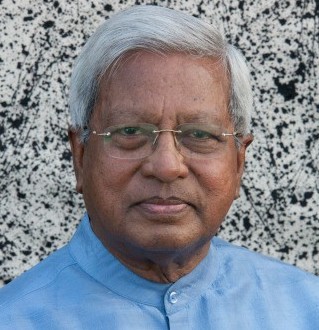

Sir Fazle Abed

Bangladesh

Sir Fazle Hasan Abed of Bangladesh, the internationally renowned founder and chairperson of BRAC, was honored as the 2015 World Food Prize Laureate for his unparalleled achievement in building a unique, integrated development organization that many have hailed as the most effective anti-poverty organization in the world.

Full Biography

Soon after founding BRAC in 1972, Sir Fazle began focusing on the social and economic empowerment of women, which was a new, breakthrough approach to lifting the poor out of poverty. He was determined to find ways to provide rural village and farm women with the tools they needed to take control of their lives and become change agents in their communities. In addition to microcredit programs that provided small loans to women, BRAC launched a sustainable agriculture project in Bangladesh based on poultry farming. Two decades later, the poultry project involved 1.9 million women, and had managed to establish commercial and social linkages that connected local activities to the wider national economy, and introduced women to the experience of making real profits.

Under Sir Fazle’s leadership of more than 40 years, BRAC’s agricultural and development innovations have improved food security for millions and contributed to a significant decline in poverty levels through direct impacts to farmers and small communities across the globe.

The agriculture and food security programs developed by Sir Fazle and BRAC have helped more than 500,000 farmers gain access to efficient farming techniques, proven technologies and financial support services. Through farmers’ participation in field demonstrations and training, these programs have helped increase yields through crop intensification, research and development on new seed varieties and provision of quality seeds at fair prices.

BRAC’s multi-dimensional and dynamic methods of reducing hunger and poverty include the creation and support of a range of integrated enterprises, such as: seed production and dissemination; feed mills, poultry and fish hatcheries; milk collection centers and milk processing factories; tea plantations; and packaging factories. The income generated from these social enterprises is used to subsidize primary schools and essential health care.

Through his visionary work, Sir Fazle has demonstrated a profound understanding of the role that agriculture plays in development as well as the complexities that perpetuate poverty. Over the decades, he has worked tirelessly to confront poverty by creating an enabling environment to achieve food security at the family and the community levels, and to help generate productive employment and income for poor households to enable them to access nutritious food.

Early Life, Education and Career

Fazle Hasan Abed was born into a distinguished family in 1936 in Baniachong, in Bangladesh’s Habiganj district. His maternal grandfather was a minister in the colonial government of Bengal; a great-uncle was the first Bengali to serve in the governor of Bengal’s executive council. He attended Pabna Zilla School and went on to complete his higher secondary education at Dhaka College.

Abed, as he is known to family and friends, attended the University of Glasgow in Scotland where he studied naval architecture. Following that, he pursued further education and a career path in accounting, graduating from the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants in London in 1962. It was during this time that he also developed an interest in world literature, reading the works of Shakespeare, Homer, Virgil, Dante, Goethe, and Rilke. He is quoted as saying: “My love affair with English and European literature continued for almost a decade.” He also developed a taste for Western classical music such as Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven.

Abed returned to his homeland in 1969, accepting a position with the Shell Oil Company in Chittagong. In just two years, he was promoted to head of the company’s accounting department and was living the comfortable lifestyle of a corporate executive. In 1970-71, however, his life—and the lives of millions of Bangladeshis—changed as the result of two very dramatic events: a deadly tropical cyclone, which swept across the country, washing away farms, villages, and towns in its path; followed by the nine-month war of independence from Pakistan. The combined death toll from the storm and the war was estimated at well over 3 million people. An additional 10 million were displaced and further impoverished.

Abed resigned from Shell Oil in 1971, and the next year formed the Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee (BRAC’s original name) to address the terrible devastation suffered by the people of his country. Following initial relief efforts, the organization soon became involved in more long-term community development, with primary objectives of alleviation of poverty and empowerment of the poor—and was renamed the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee.

Abed was concerned from the very beginning that his organization should not foster an attitude among the poor of dependence on others for daily, or year-to-year, assistance. He realized that implementing successful strategies to reduce hunger and poverty would require a deeper understanding of the underlying social and economic circumstances.

With his strong focus on growing its operations across a broad spectrum of agricultural, economic, and social enterprises, Abed set BRAC on a course that was different from other non-governmental organizations. He had concluded that economic development was one of the keys to helping the rural poor—and thus launched a microfinance program to provide very small loans to women borrowers as part of village support groups that participated in skills and organizational training.

Leadership of BRAC - Innovative, Visionary, Resilient and Resourceful

|

From the start, Abed directed his efforts toward helping the poor to develop their capacity to manage and control their own destiny. To that end, he has always sought new and multi-faceted ways to address social problems. He encouraged researchers and staff to spend a lot of time in the field learning about the on-ground challenges and then tailoring innovative techniques and programs to meet those challenges.

A program director has commented that “BRAC encourages you to experiment and learn from your mistakes. It gives its people room to grow. If you identify a social need, you can try to build a development program to fulfill that need.”

Thinking local and acting global, BRAC has spread its antipoverty solutions to ten other developing countries besides Bangladesh, including Uganda, Tanzania, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Liberia, Haiti, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the Philippines.

In the area of agriculture, Abed’s leadership has led to extraordinary advancements in the poultry, seed, and dairy industries in Bangladesh, and has forged a path for progress in the global agricultural sector, enhancing food quality and security across the developing world.

The objectives of BRAC’s agriculture and food security program have been to increase crop and livestock production while ensuring environmental sustainability, adaptability to climate change, and affordability for marginal and small farmers. Essential to this approach is ensuring that improved inputs and technologies are taken to the poor farmers—and that the experience of the farmers is brought back to the laboratories—in a continual cycle of innovation.

During the mid-1970s, Abed and his team of colleagues had observed that local Bangladesh homegrown chickens were small and sickly compared to their commercial competitors, and did not yield as many eggs. The cause was linked to a lack of quality feed and minimal access to poultry vaccines. To address this problem, Abed invested in producing affordable vaccines and had an ingenious solution to preserving the vaccines inside of bananas, a low-cost solution that utilized abundant local resources. As healthy, vaccinated chicks became more plentiful, there was a growing need for high-quality and inexpensive poultry feed. Abed intervened again to cultivate and distribute maize as a practical and sustainable feed source. The result was a massive increase in productivity and efficiency in the poultry industry.

As BRAC has grown into the largest NGO in the world, Sir Fazle has ensured that it seamlessly integrated development assistance with a market-oriented, self-sustaining approach, often using social enterprises to improve the agricultural sector. In addition to the poultry model, for example, BRAC originated seed processing plants in Bangladesh, which process around 5,500 metric tons of high-yield rice, maize and other vegetable seeds, allowing self-employed seed distributors to offer prices for agricultural inputs that are fair for buyers and seller alike. The organization opened a similar unit, using the same micro-franchised, hub-and-spoke distribution network, in 2012 in Uganda.

Sir Fazle’s foresight and vision has led BRAC to invest heavily in agricultural research and development. Its R & D centers work closely with national and international research organizations to develop high-yielding hybrid, as well as climate-resilient, crop varieties. Notable is the work on salt- and submergence-tolerant rice that can be grown in flood-prone areas, and the introduction of maize and sunflower in fallow land areas to increase food availability.

The global reach of BRAC is unprecedented, with more than 110,000 employees around the world, and a further 150,000 BRAC-trained entrepreneurs providing low-cost goods and services (such as seeds, medicine and training) to their rural neighbors.

In times of uncertain food security as the world’s population is projected to burgeon to more than 9 billion people by 2050, BRAC’s triumphal programs are scalable and sustainable, many of them in the form of enterprises that deliver a “dual bottom line” of a financial profit and a social good.

Through BRAC, Sir Fazle has been a leader in empowering women and girls through microfinance, education, healthcare, and encouraging their active participation in directing village life and community cohesion. “We have always used an approach to development that puts power in the hands of the poor themselves, especially women and girls,” he said. “Educated girls turn into empowered women, and as we have seen in my native Bangladesh and elsewhere, the empowerment of women leads to massive improvements in quality of life for everyone, especially the poor.”

BRAC has recently increased its commitment to girls’ education in low-income countries with a five-year pledge to reach 2.7 million additional girls through primary and pre-primary schools, teacher training, adolescent empowerment programs, scholarships and other programs.

The Chairman of the World Food Prize Selection Committee and the first World Food Prize Laureate in 1987, Dr, M.S. Swaminathan, has praised Sir Fazle Hasan Abed as a “strategic thinker, and a man with a future vision.”

Dr. Swaminathan lauded BRAC and its founder, writing that:

“While it was set up in the context of the post-war reconstruction in Bangladesh, and its initial focus was on basic needs and strengthening livelihoods, Abed soon realized that the better strategy would be to complement state efforts rather than repeating them.

BRAC is constantly innovating. While funding was important, Abed realized that the organization needed some internal financial resources in order to steer its course, rather than become diverted by donor agendas. He therefore set up a considerable number of commercial enterprises as part of the BRAC ‘brand.’ These include printing presses, poultry and dairy industries, a hotel, conference facilities, retail outlets and the private BRAC University, among others. Surpluses from these enterprises go into supporting BRAC’s development programs.”

And finally, Dr. Paul Collier, professor of Economics at Oxford University and author of The Bottom Billion, summed it up when he called BRAC “the most astounding social enterprise in the world.”