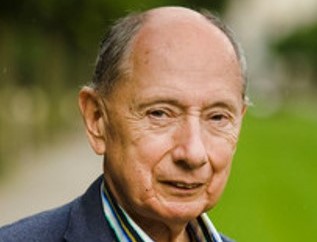

Dr. Marc Van Montagu

BELGIUM

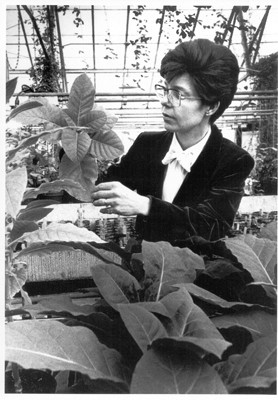

Dr. Mary Dell Chilton

UNITED STATES

Dr. Robert Fraley

UNITED STATES

Brief Synopsis

Dr. Marc Van Montagu, Dr. Mary Dell Chilton, and Dr. Robert Fraley share the 2013 World Food Prize for their individual breakthrough achievements in founding, developing, and applying modern agricultural biotechnology. Their research has made it possible for farmers to grow crops with: improved yields; resistance to insects and disease; and the ability to tolerate extreme variations in climate.

Full Biographies

Dr. Marc Van Montagu

Born in 1933 in Ghent, Belgium, Marc Van Montagu grew up during the Second World War, a time when food rationing and general hardships were common among most of that country’s population. Despite his family’s economic difficulties throughout the war and post-war period, they were able to send their only child to good primary and secondary schools. His excellent teachers in high school triggered Van Montagu’s enthusiasm for organic chemistry and biology.

Later, as a student at Ghent University, he became intrigued with the new science of molecular biology, particularly the functions of DNA and RNA, which had recently been discovered to be present in all living organisms. Van Montagu’s path of study and scientific experimentation culminated in a Ph.D. in organic chemistry/biochemistry in 1965. This led to a permanent position with the Cell Biology Department at Ghent University Medical School, where he focused his research on RNA bacteriophages with his colleague Walter Fiers.

In the late 1960s, Van Montagu and his fellow researcher Jeff Schell (1935-2003) started working with the plant disease known as crown gall. They were the first to discover, in 1974, that Agrobacterium tumefaciens, the plant tumor-inducing soil microbe, carries a rather large circular molecule of DNA, which they named "Ti plasmid." They demonstrated that this plasmid is responsible for formation of the plant tumor. Later, they, and Mary-Dell Chilton and her research team at the University of Washington, demonstrated that a segment of this plasmid, the T-DNA, is copied and transferred into the genome of the infected plant cell.

Van Montagu and Schell’s elucidation of the structure and function of Ti plasmid led to their development of the first technology to stably transfer foreign genes into plants. This discovery galvanized the emerging molecular biology community, and set up a race to develop workable plant gene tools that could genetically engineer an array of plants and greatly enhance crop production worldwide. Their landmark discovery provided scientists with an appropriate tool, or vector, to pursue complex biological questions in terms of specific genes, their structure, and the control of their expression in all aspects of plant biology.

Plant biotechnology as a new phenomenon rocketed to the forefront of the scientific world in 1983 when Van Montagu and two other scientists who would someday share The World Food Prize with him – Chilton and Robert T. Fraley – each presented the results of their independent, pioneering research on the successful transfer of bacterial genes into plants and the creation of genetically modified plants at the Miami Biochemistry Winter Symposium: "Advances in Gene Technology."

Van Montagu went on to found two biotechnology companies: Plant Genetic Systems, best known for its early work on insect-resistant and herbicide tolerant crops; and Crop Design, a company focused on the genetic engineering of agronomic traits for the global commercial corn and rice seed markets.

In 2000, he also founded the Institute of Plant Biotechnology Outreach with the mission to assist developing countries in gaining access to the latest plant biotechnology developments and to stimulate their research institutions to become independent and competitive.

The pioneering work of Marc Van Montagu, Chilton and Fraley contributed to the emergence of a new term, "agricultural biotechnology," and set the stage for engineering crops with novel traits that improved yields and conferred resistance to insects and disease, as well as tolerance to adverse environmental conditions. By 2013, their work had made it possible for farmers in more than 30 countries to improve the yields of their crops, increase their incomes, and feed a growing global population.

Beginning with the first cultivation of staple transgenic crops in 1996, biotech crops have contributed to food security and sustainability by increasing crop production and providing a better environment by reducing the application of significant amounts of pesticides worldwide. By 2013, approximately 12 percent of the world’s arable land had been planted with biotechnology crops.

There have been dramatic increases in the total worldwide acreage planted. Corn, soybeans, canola and cotton are the major biotech crops grown commercially on a large scale and have become an integral part of international agricultural production and trade. At the same time, a wide variety of useful genes have been transferred into a large number of economically important plants, including most of the food crops, scores of varieties of fruits and vegetables, and many tree species.

According to a report by ISAAA (International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications), 2012 marked the first year since the introduction of biotech crops that developing countries grew more biotech crops than industrial countries. This has contributed to enhanced food security and poverty reduction in some of the world’s most vulnerable regions. The report states: "In the period 1996 to 2012, millions of farmers in 30 countries planted an accumulated 1.5 billion hectares."

A record 17.3 million farmers grew biotech crops worldwide in 2012, with over 90 percent of them resource-poor smallholder farmers in developing countries. Through their planting and harvesting of biotech crops, more than 15 million smallholder farmers and their families, totaling approximately 50 million people, were able to increase their incomes and reduce poverty conditions. In the Philippines alone, more than one-third of a million smallholder farmers benefited from biotech maize. During the period 1996-2011, according to the ISAAA report, 328 million tons of additional food, feed and fiber was produced worldwide as biotech crops.

For his breakthrough achievement as a pioneer of biotechnology, Van Montagu was awarded the 2013 World Food Prize, along with Drs Mary-Dell Chilton and Robert T. Fraley. As the world grapples with how to feed the estimated 9 billion people who will inhabit the planet by the year 2050, it will be critical to continue building upon the scientific advancements and revolutionary agricultural discoveries of the 2013 World Food Prize Laureates.

Dr. Mary-Dell Chilton

Born in Indianapolis in 1939, Mary-Dell Chilton took her first biology class in seventh grade and surprised her teachers by scoring extremely high on a national science exam. While in high school, Chilton decided to concentrate her educational goals on math and science. She also became an amateur telescope maker who was deeply interested in optics.

Born in Indianapolis in 1939, Mary-Dell Chilton took her first biology class in seventh grade and surprised her teachers by scoring extremely high on a national science exam. While in high school, Chilton decided to concentrate her educational goals on math and science. She also became an amateur telescope maker who was deeply interested in optics.

In college, Chilton studied the chemical basis of biological specificity, which, to her delight, addressed numerous questions that had no answers – and therefore offered the possibility of discovery. The direction of her life’s work in molecular genetics and plant biotechnology became clear while she pursued her Ph.D. in chemistry at the University of Illinois.

The Double Helix structure of DNA fascinated her, and, after completing her doctoral thesis on bacterial transformation, showing that both strands of the Helix can "fix" a cell, she accepted a postdoctoral position in microbiology at the University of Washington (UW) in Seattle. It was there that she learned DNA hybridization technology, a collection of tools that served her well in her next undertaking – a study of how Agrobacterium causes plant cells to grow into a tumor, or gall.

In the race to build upon the work of Marc Van Montagu and Jeff Schell in Belgium, Chilton and two colleagues at UW – Milton Gordon and Eugene Nester – made the breakthrough discovery that the crown gall tumors of plants were caused by the transfer of only a small piece of DNA from the Ti plasmid (T-DNA) in Agrobacterium tumefaciens into the host plant, where it became part of the plant’s genome.

Chilton continued her molecular biology research at Washington University in St. Louis, accepting a faculty position there in 1979. Three years later, her team harnessed the gene-transfer mechanism of Agrobacterium to produce the first transgenic tobacco plant, and she reported these startling findings at the 1983 Miami Winter Biochemistry Symposium. Chilton’s work demonstrated that T-DNA can be used to transfer genes from other organisms into plants. Thus, her work provided evidence that plant genomes could be manipulated in a much more precise fashion than was possible using traditional plant breeding.

Chilton was hired by Ciba-Geigy Corporation (later Syngenta Biotechnology, Inc., or SBI) at Research Triangle Park in North Carolina in 1983 and began the next phase of her career, spanning both biotechnology research and administrative roles including Vice President of Agricultural Biotechnology, Distinguished Science Fellow, and Principal Scientist.

Chilton established one of the world’s first industrial agricultural biotechnology programs, leading applied research in areas such as disease and insect resistance, as well as continuing to improve transformation systems in crop plants. At the time she received The World Food Prize in 2013, along with fellow scientists Van Montagu and Robert T. Fraley, she had spent the past three decades overseeing the implementation of the new technology she developed and further improving it to be used in the introduction of new and novel genes into plants. In 2015, she was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

The pioneering work of Mary-Dell Chilton, Marc Van Montagu, and Robert T. Fraley contributed to the emergence of a new term, "agricultural biotechnology," and set the stage for engineering crops with novel traits that improved yields and conferred resistance to insects and disease, as well as tolerance to adverse environmental conditions. Their work has made it possible for farmers in more than 30 countries to improve the yields of their crops, increase their incomes, and feed a growing global population.

Beginning with the first cultivation of staple transgenic crops in 1996, biotech crops have contributed to food security and sustainability by increasing crop production and providing a better environment by reducing the application of significant amounts of pesticides worldwide. By 2013, approximately 12 percent of the world’s arable land had been planted with biotechnology crops.

There have been dramatic increases in the total worldwide acreage planted. Corn, soybeans, canola and cotton are the major biotech crops grown commercially on a large scale and have become an integral part of international agricultural production and trade. At the same time, a wide variety of useful genes have been transferred into a large number of economically important plants, including most of the food crops, scores of varieties of fruits and vegetables, and many tree species.

According to a report by ISAAA (International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications), 2012 marked the first year since the introduction of biotech crops that developing countries grew more biotech crops than industrial countries. This has contributed to enhanced food security and poverty reduction in some of the world’s most vulnerable regions. The report states: "In the period 1996 to 2012, millions of farmers in 30 countries planted an accumulated 1.5 billion hectares."

A record 17.3 million farmers grew biotech crops worldwide in 2012, with over 90 percent of them resource-poor smallholder farmers in developing countries. Through their planting and harvesting of biotech crops, more than 15 million smallholder farmers and their families, totaling approximately 50 million people, were able to increase their incomes and reduce poverty conditions. In the Philippines alone, more than one-third of a million smallholder farmers benefited from biotech maize.

During the period 1996-2011, according to the ISAAA report, 328 million tons of additional food, feed and fiber was produced worldwide as biotech crops. As the world grapples with how to feed the estimated 9 billion people who will inhabit the planet by the year 2050, it will be critical to continue building upon the scientific advancements and revolutionary agricultural discoveries of the 2013 World Food Prize Laureates.

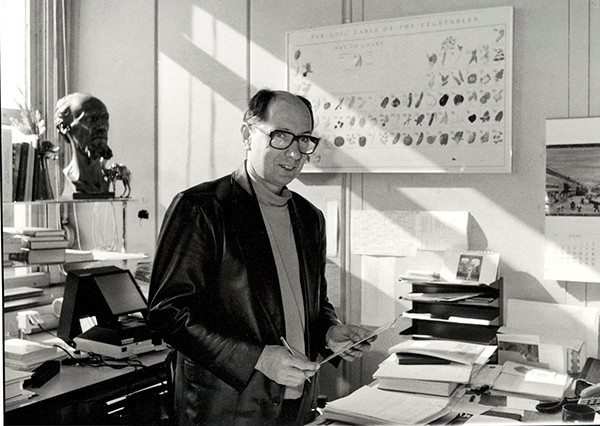

Dr. Robert T. Fraley

Born in 1953 in Wellington, Illinois, Robert T. Fraley earned a Ph.D. in microbiology/biochemistry from the University of Illinois in 1978. Fraley’s passion for helping farmers grow better and higher yielding crops was shaped by his experience growing up on a small Midwestern farm that produced grains and livestock. As a child exploring the world around him in rural Illinois, his interest in the scientific complexities of living organisms developed very early and blossomed during his college education and graduate training in microbiology and biochemistry at the University of Illinois and his post-doctoral research in biophysics at the University of California-San Francisco.

Born in 1953 in Wellington, Illinois, Robert T. Fraley earned a Ph.D. in microbiology/biochemistry from the University of Illinois in 1978. Fraley’s passion for helping farmers grow better and higher yielding crops was shaped by his experience growing up on a small Midwestern farm that produced grains and livestock. As a child exploring the world around him in rural Illinois, his interest in the scientific complexities of living organisms developed very early and blossomed during his college education and graduate training in microbiology and biochemistry at the University of Illinois and his post-doctoral research in biophysics at the University of California-San Francisco.

Hired by Monsanto in 1981 as a research specialist, Fraley led a plant molecular biology group that worked on developing better crops through genetic engineering to give farmers real solutions to critical problems such as the pest and weed infestations that frequently destroyed crops. His early research built upon the biotechnology discoveries of plant scientists Mary-Dell Chilton and Marc Van Montagu as he focused on inventing effective methods for gene transfer systems.

A breakthrough occurred when Fraley and his team isolated a bacterial marker gene and modified it so that it could affect another plant. By inserting that gene into Agrobacterium, they were able to have the Agrobacterium carry that gene into petunia and tobacco cells, thus installing a new immunity trait. Fraley and his team thus produced the first transgenic petunia plants using the Agrobacterium transformation process, and presented these findings at the Miami Biochemistry Winter Symposium in 1983.

Raised on a farm, Fraley could readily see the potential that this emerging science offered to farmers across many countries, many crops, and farms of all sizes. To better understand farmers’ needs regarding the application of biotechnology to agriculture, he often went out into fields to observe local agronomic practices and talk with farmers to ensure that they would be offered solutions that worked better than any alternatives.

With his team of researchers, Fraley developed elaborate plant transformations of an array of crops, leading to the widespread accessibility of farmers across the globe to genetically modified seeds with resistance to insect and weed pests, and with tolerance to changes in climate such as excessive heat and drought. Plant breeders now have the ability to understand the genetic composition of every seed, and farmers have more tools than ever before to ensure that they can grow higher-yielding crops.

In 1996, Fraley led the successful introduction of genetically engineered soybeans that were resistant to the herbicide glyphosate, commercially known as Roundup. When planting these "Roundup Ready" crops, a farmer was able to spray an entire field with glyphosate and only the weeds would be eliminated, leaving the crop plants alive and thriving.

In leadership positions at Monsanto, as Executive Vice President and Chief Technology Officer, Fraley played a key role in the company’s choice of research directions that led to viable finished products, and the technical and business strategy that ensured wide availability and benefit to large- and small-scale farmers around the world. He has especially championed improving accessibility of biotechnology to smallholder farmers.

The individual, pioneering work of the three 2013 World Food Prize Laureates – Robert T. Fraley, Marc Van Montagu, and Mary-Dell Chilton - contributed to the emergence of a new term, "agricultural biotechnology," and set the stage for engineering crops with novel traits that improved yields and conferred resistance to insects and disease, as well as tolerance to adverse environmental conditions. By 2013, their work had made it possible for farmers in more than 30 countries to improve the yields of their crops, increased their incomes, and feed a growing global population.

Beginning with the first cultivation of staple transgenic crops in 1996, biotech crops have contributed to food security and sustainability by increasing crop production and providing a better environment by reducing the application of significant amounts of pesticides worldwide. By 2013, approximately 12 percent of the world’s arable land had been planted with biotechnology crops.

There have been dramatic increases in the total worldwide acreage planted. Corn, soybeans, canola and cotton are the major biotech crops grown commercially on a large scale and have become an integral part of international agricultural production and trade. At the same time, a wide variety of useful genes have been transferred into a large number of economically important plants, including most of the food crops, scores of varieties of fruits and vegetables, and many tree species.

According to a report by ISAAA, (International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications), 2012 marked the first year since the introduction of biotech crops that developing countries grew more biotech crops than industrial countries. This has contributed to enhanced food security and poverty reduction in some of the world’s most vulnerable regions. The report states: "In the period 1996 to 2012, millions of farmers in 30 countries planted an accumulated 1.5 billion hectares."

A record 17.3 million farmers grew biotech crops worldwide in 2012, with over 90 percent of them resource-poor smallholder farmers in developing countries. Through their planting and harvesting of biotech crops, more than 15 million smallholder farmers and their families, totaling approximately 50 million people, were able to increase their incomes and reduce poverty conditions. In the Philippines alone, more than one-third of a million smallholder farmers benefited from biotech maize.

During the period 1996-2011, according to the ISAAA report, 328 million tons of additional food, feed and fiber was produced worldwide as biotech crops. As the world grapples with how to feed the estimated 9 billion people who will inhabit the planet by the year 2050, it will be critical to continue building upon the scientific advancements and revolutionary agricultural discoveries of the 2013 World Food Prize Laureates.

Additional Links

2013 Laureate Luncheon Address Transcript

Dr. Marc van Montagu - Ted Talk