How Receiving the World Food Prize Had an Impact on My Work

|

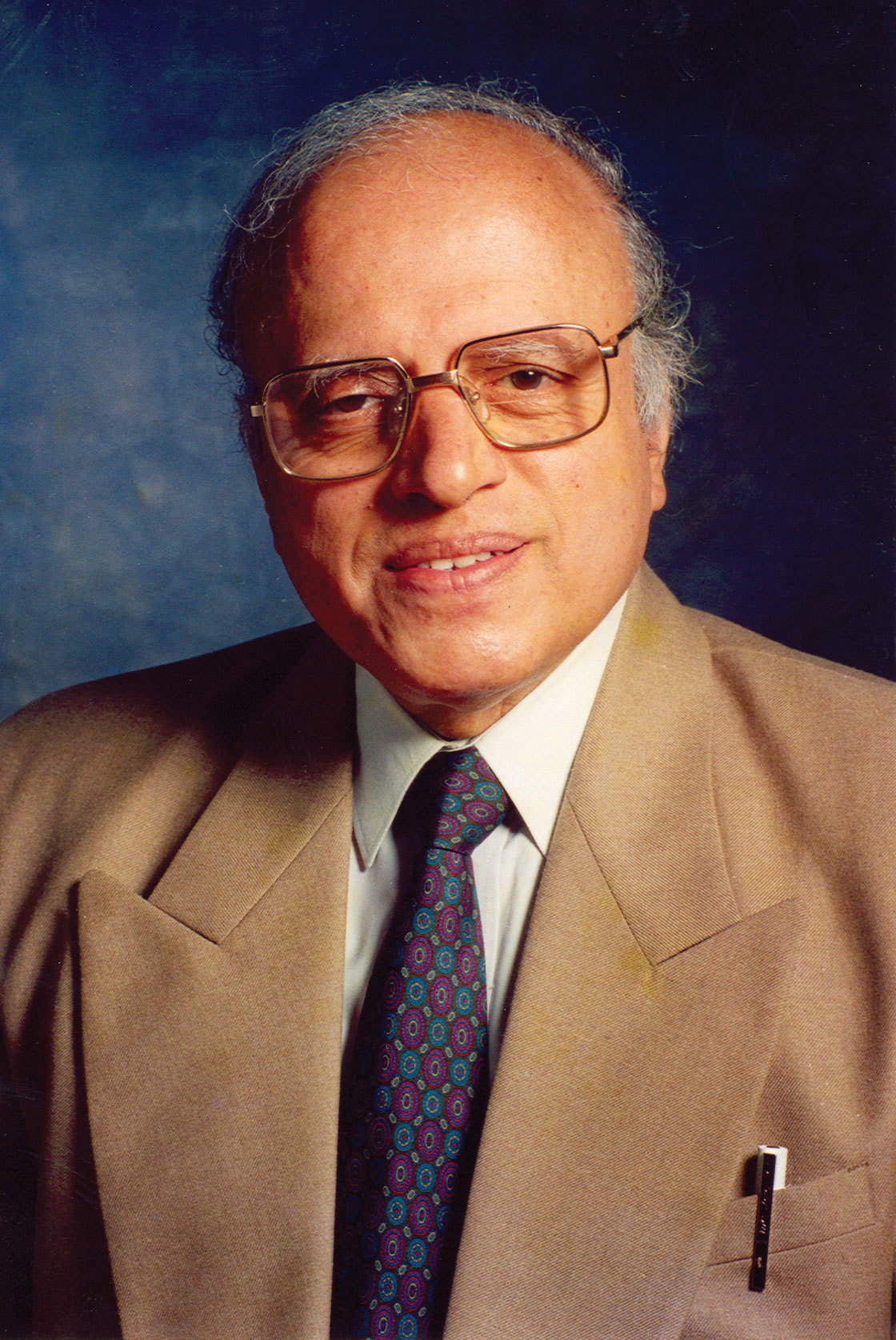

| Dr. M. S. Swaminathan |

I felt extremely honored when I received the first World Food Prize in 1987 for several reasons. This prize was established with great difficulty by Dr. Norman Borlaug who first tried without success to establish a Nobel Prize in Food and Agriculture. Fortunately, over the years, thanks to the efforts of Ambassador Kenneth Quinn, the World Food Prize is now regarded as equivalent to a Nobel Prize.

The financial amount associated with the prize helped me to establish a research center at Chennai, India named M. S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF). This center, based on a pro-nature, pro-poor and pro-women orientation, emphasizes technology development and dissemination and has filled the gaps in several parts of India between scientific know-how and field level do-how. The center concentrates on three areas of research: participatory research with farming and tribal families; anticipatory research to prepare farmers for the adverse impact of temperature and rising sea levels; and translational research to link scientific knowledge with field application. All the work done by MSSRF has been human centered and has received widespread recognition, as for example the Blue Planet Prize by the Asahi Foundation. MSSRF is the first and only research organization which has received the prize in Asia so far.

The work on participatory research led to the breeding of an outstanding rice variety, named Kalajeera, which is a product of cooperation between tribal families in the Koraput area of Odisha and MSSRF scientists. In the field of anticipatory research, MSSRF has shown how to overcome the problems of rising sea levels by developing methods for sea water farming for coastal area prosperity. A genetic garden of halophytes has been established for this purpose.

In translational research, considerable work has been done in the field of nutrition security. An important contribution has been the establishment of genetic gardens of biofortified plants which can help to mitigate hidden hunger caused by micronutrient deficiency. Thus the World Food Prize has helped the initiation of several programs meaningful to achieving the zero hunger challenge of Norman Borlaug.

Taking new technologies to those who have not benefited from them so far has been a priority in MSSRF’s research agenda. Thus, in the area of ICT, village knowledge centers based on the integrated use of the internet and mobile telephone have been established. Fishermen going in small boats are informed before they leave the shore what the wave heights will be at different distances from the coast.

In order to provide a sense of self-esteem to semi-literate rural women, a National Virtual Academy has been established and many of the rural and tribal women are fellows of the Academy. The strategy of MSSRF in relation to women’s empowerment is to make them highly skilled. In the villages where MSSRF works, women will be proud to say they are Community Hunger Fighters, Academicians, Plant Doctors, Biodiversity Conservers, Climate Risk Managers, etc. This is the only way of achieving gender equality and women’s progress in agriculture and allied fields.

More recently, MSSRF has taken on a large program for leveraging agriculture for nutrition. India has the largest number of malnourished women and children in the world, and MSSRF’s work has shown that hunger and malnutrition can be made problems of the past by combining the approaches of Norman Borlaug with new technologies.