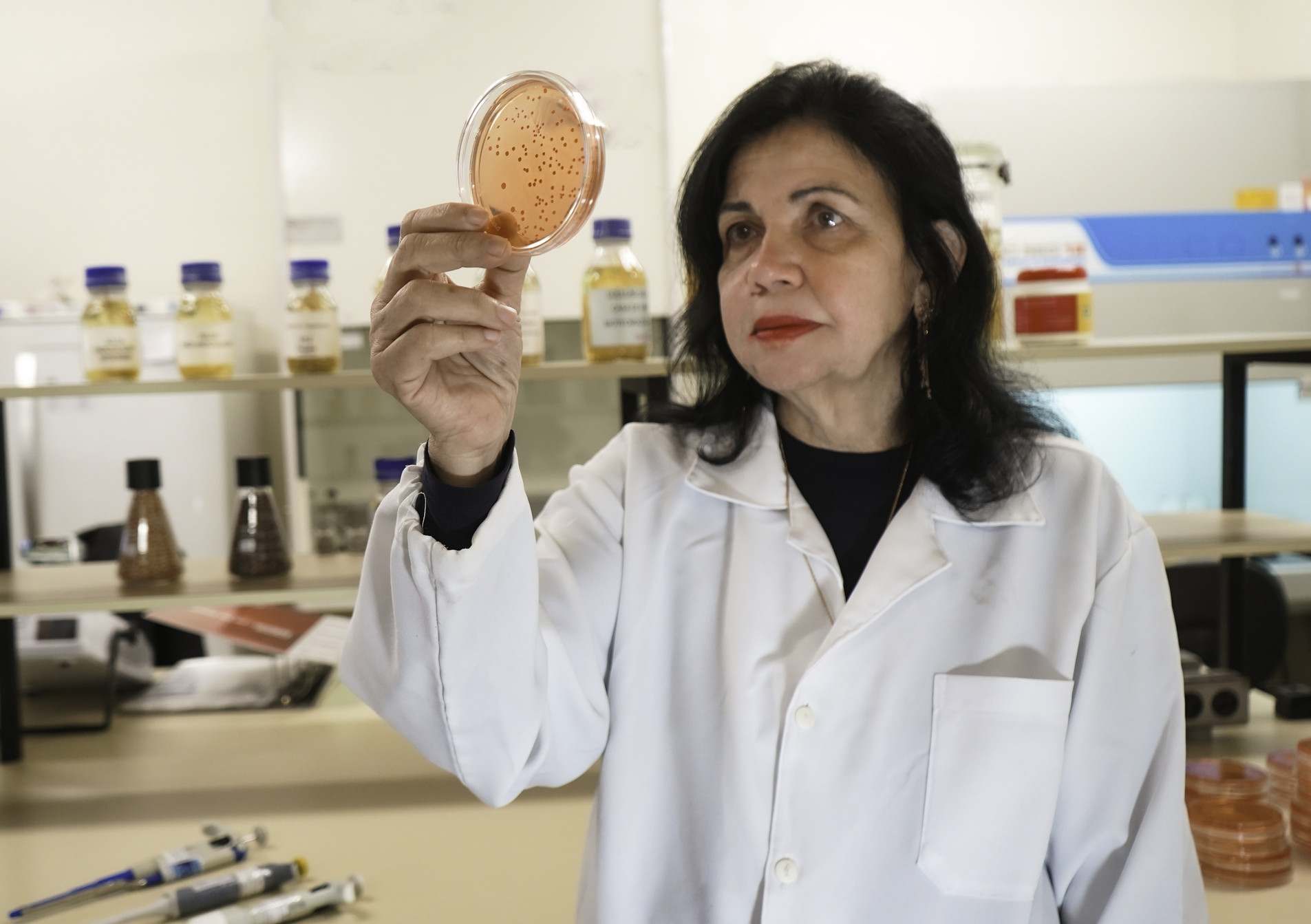

Mariangela Hungria

BRAZIL

Dr. Mariangela Hungria will receive the 2025 World Food Prize for her extraordinary scientific advancements in biological nitrogen fixation, transforming the sustainability of soil health and crop nutrition for tropical agriculture. The low-cost technologies and products that she has developed have increased crop productivity affordably and sustainably across tens of millions of hectares. By harnessing symbiotic soil microorganisms as an effective alternative to synthetic fertilizers, she has not only improved plant nutrient uptake but also enabled farmers to save billions of dollars while mitigating environmental risks associated with pollution and emissions—producing more with less.

Links:

Laureate story | Press Advisory | Press Release

Photos | Social Media Kit

2025 Laureate Announcement

2025 Laureate Award Ceremony - Coming Soon!

Laureate Video - Coming Soon!

Biography

Hungria entered college in the late 1970s to study microbiology, at a time when soil science was overwhelmingly focused on the use of chemical fertilizers to recover and maintain soil fertility and soil microbiology was considered of minor importance. Her persistence, dedication and scientific rigor throughout her career greatly elevated the importance of soil microbes in the agriculture sector and demonstrated to farmers and scientists that soil fertility should be built with life, not just with chemicals.

“The 1970s had witnessed the significant Green Revolution led by Norman Borlaug, which dramatically increased agricultural production through the intensive use of chemical fertilizers, particularly nitrogen-based ones,” said Hungria. “However, I was already working on a different strategy—using microorganisms as biofertilizers, envisioning that they could drive a Micro Green Revolution, enhancing agricultural productivity with environmental responsibility.”

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for plant growth and production which is often supplied in agriculture by chemical fertilizers. However, chemical nitrogen fertilizer overuse often results in higher emissions and water pollution with nitrates. Hungria’s research principally focused on biological nitrogen fixation, a process by which naturally occurring microorganisms interact with plants to fix nitrogen from the air into the soil, where it can then be taken up by plant roots.

Hungria saw an opportunity to use bacteria to supply nitrogen, which would mitigate the environmental impact of agriculture and allow farmers to reduce their reliance on costly, imported fertilizers. Over decades of research and development at Embrapa Soja - the National Soybean Center of Brazil, Hungria built her field of study from the ground up. She isolated strains of bacteria and tested them for their potential to promote plant growth. She led the development of more than 30 technologies related to microorganisms, including many microbial inoculants, products containing beneficial bacteria that are applied to seeds or soils, for soybeans, common beans, maize, wheat, rice, pasture grasses and other major crops.

As a field researcher, she worked with farmers to learn what they needed and teach them the uses and economic and environmental benefits of bacteria for crop growth. As a microbiology professor, she trained and mentored young researchers, many of them women. As a science communicator, she published more than 500 scientific articles, technical manuals, books and book chapters.

As a field researcher, she worked with farmers to learn what they needed and teach them the uses and economic and environmental benefits of bacteria for crop growth. As a microbiology professor, she trained and mentored young researchers, many of them women. As a science communicator, she published more than 500 scientific articles, technical manuals, books and book chapters.

Hungria’s work has contributed significantly to making Brazil the global leader in the commercial use of biological inoculants. The technologies she and her research group developed have been adopted worldwide, including on more than 40 million hectares in Brazil. These innovations have saved Brazilian farmers around $25 billion per year in input costs, prevented the release of 230 million metric tons of CO2-equivalent emissions, and boosted yields beyond what is possible with synthetic nitrogen fertilizer alone. This achievement, along with other scientific advances, has propelled Brazil to become the world’s leading soybean producer and exporter—laying the foundation for the country’s agricultural and economic growth over the past several decades.

“For many years—years in which I built my career—the prevailing concept was to produce food to end world hunger. The focus was solely on producing more and more. However, contrary to the dominant thinking at the time, I always worked with the concept of producing food sustainably, which is finally gaining greater credibility each year. Today, there is a growing global demand for increased food production and quality, but with sustainability—reducing soil and water pollution and lowering greenhouse gas emissions,” Hungria said.

RESEARCHING RHIZOBIA

While earning her doctorate at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro, Hungria studied under her mentor, Dr. Johanna Döbereiner, an influential initial proponent of using microorganisms in tropical agriculture. With the skills she learned from Döbereiner, Hungria settled in Londrina in Paraná state to start a new soil microbiology laboratory at the Embrapa National Soybean Center in 1991.

At the time, almost no research existed on using biological nitrogen fixation to produce soybeans in the tropics, so Hungria built her ambitious research program from scratch. She first concentrated on selecting elite strains of rhizobia, a type of symbiotic bacteria that forms nitrogen-fixing nodules on the roots of legumes like soybeans and common beans. She then monitored the effects of introducing these strains to plants (called inoculation) on enhancing crop yield, tested and verified the effects of environmental stresses on the inoculants’ performance, and selected plant genotypes with a better response to microorganisms. She took a “basic to applied” approach to soil microbiology, starting with studies on bacteria evolution all the way through to the development of microbial inoculants for farmers’ use.

Existing research in the U.S., Australia and Europe had shown that a single inoculation in soybeans did not result in the hoped-for yields equal to those reaped with chemical fertilizer. Hungria, always determined, did not stop there with her experiments. She showed that inoculating soybeans each growing season ensured ready availability of the beneficial bacteria in the soil. Reinoculation each season finally succeeded in producing an eight percent growth in yield over conventional chemical inputs.

Existing research in the U.S., Australia and Europe had shown that a single inoculation in soybeans did not result in the hoped-for yields equal to those reaped with chemical fertilizer. Hungria, always determined, did not stop there with her experiments. She showed that inoculating soybeans each growing season ensured ready availability of the beneficial bacteria in the soil. Reinoculation each season finally succeeded in producing an eight percent growth in yield over conventional chemical inputs.

In the spirit of Norman Borlaug’s “take it to the farmer” philosophy and vision, Hungria spent as much time in the field working with farmers as she did in the lab advancing her scientific research. She participated in field days, led training during extension activities and wrote technical pamphlets. In 1994, she wrote the first Portuguese-language manual for tropical soil microbiology methods. This manual and others she wrote helped industrial manufacturers implement methodologies and protocols for inoculant production.

“As a professional, I learned to do science for the farmer—applying scientific concepts to investigate and solve real-world agricultural problems. A participatory science, where I would go to the farmers to understand their challenges and expectations, then return to the laboratory to find solutions,” Hungria said. “Later, I would present these solutions, invest heavily in disseminating and popularizing the technologies, and monitor their outcomes. This combination of "basic to applied science" became the defining feature of the research group I started to build—one that spans from genome to field, from microorganism selection to bio-inputs on the shelf.”

Hungria’s diligent scientific research and open communication with farmers and industry resulted in a quick uptake of microbial inoculation among soybean producers. Today, this technology is used annually on 85 percent of Brazil’s total cultivated area of soybeans, more than 30 million hectares—the highest inoculation adoption rate in the world.

In addition to having a beneficial environmental effect, this has significantly reduced farmers’ costs. Farmers may use 30-50 kilograms of synthetic fertilizer per hectare at a cost of about US$1 per kilogram. By contrast, farmers spend as little as US$2-3 per hectare on the bacteria inoculant, which can supply the complete nitrogen needs of the crop.

APPLYING AZOSPIRILLUM

The increasing success of inoculation in soybeans had farmers requesting microbial inputs for other crops as well. In response to this need, Hungria incorporated a new line of research on bacteria for non-leguminous crops. Her research identified promising strains of the bacterium Azospirillum brasilense, which fixes nitrogen and produces phytohormones which promote plant growth.

These studies led to the release of the first commercial strains of A. brasilense which were used to formulate biological inoculants to promote the growth of maize, wheat and rice. Today, this inoculant has been adopted on more than 14 million hectares of maize. She also created the first inoculant for grass pastures, which has the potential to restore existing pastures to health for better, more efficient cattle production, reducing the pressure to clear more land for agricultural use.

These studies led to the release of the first commercial strains of A. brasilense which were used to formulate biological inoculants to promote the growth of maize, wheat and rice. Today, this inoculant has been adopted on more than 14 million hectares of maize. She also created the first inoculant for grass pastures, which has the potential to restore existing pastures to health for better, more efficient cattle production, reducing the pressure to clear more land for agricultural use.

Her work also resulted in the first products to be released in Brazil that used a combination of microorganisms to promote plant growth. She paired nitrogen-fixing rhizobia with growth-promoting A. brasilense to double the yield increase for soybeans and common beans. The combination had a major impact on root development, improving water and nutrient absorption and increasing drought tolerance.

Hungria developed a unique method to validate the effectiveness of co-inoculation of rhizobia and A. brasilense with smallholder farmers, who cultivate soybean on less than 50 hectares and represent the majority of soybean producers in Brazil. Involving more than 3,000 farmers in a five-year study, her team confirmed that farmers using the co-inoculation made an additional profit of US$111.50 per hectare each season. They also mitigated an estimated 350 kg of CO2-equivalent per hectare from the increased production and the reduced use of chemical nitrogen fertilizers.

Today, more than 70 million doses of inoculants carrying rhizobia and A. brasilense are sold in Brazil each year. The combination is used on more than 35 percent of Brazil’s cultivated area of soybeans, about 16 million hectares.

MAKING OF A MICROBIOLOGIST

Hungria knew from a young age that she wanted to be a soil microbiologist. Her grandmother, a high school science teacher, nurtured Hungria’s interests by helping her conduct science experiments, studying insects and observing the effects of photosynthesis in the backyard. Her grandfather took her on trips out of town and showed her fields growing different types of crops.

Hungria knew from a young age that she wanted to be a soil microbiologist. Her grandmother, a high school science teacher, nurtured Hungria’s interests by helping her conduct science experiments, studying insects and observing the effects of photosynthesis in the backyard. Her grandfather took her on trips out of town and showed her fields growing different types of crops.

“When I was eight, my grandmother gave me the book Microbe Hunters by Paul de Kruif, about the lives of microbiologists,” Hungria said. “I spent the night reading in fascination. By morning, I had no doubts about what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. I wanted to be a microbiologist, but not in the medical field—it had to be about soil and plants. My fascination with agriculture was already within me.”

Graduating high school at the top of her class, she proudly declared that she wanted to go to college to study agronomy. This was an unusual choice—the other students in biology had all opted to go into the more prestigious medical field, and agronomy was a very male-dominated career path. Though her teachers tried to convince her otherwise, Hungria was not to be deterred in her passion for agriculture, and she enrolled in the Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture at the University of São Paulo.

During her undergraduate studies, she became a mother to two daughters, and for a time, it seemed that her ambition to become a soil microbiologist would be derailed. Many people told her that she would have to drop out of school, or that she could not have a successful career and also be a mother, especially as one of her daughters had special medical needs. Her grandmother, her first mentor, supported her in being both a mother and an agronomist, which gave Hungria the strength and conviction to carry on toward her dream and to support others, especially women, in shaping their professional and personal lives. She graduated third in her class with her bachelor’s degree.

Hungria’s excellent work and passion for science throughout earning her bachelor’s and master’s degrees attracted the attention of Dr. Johanna Döbereiner, a pioneer in agricultural microbiology. Döbereiner invited Hungria to do her Ph.D. at the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro and the Embrapa National Center of Agrobiology.

Though recognition of Hungria’s work was growing among Brazilian scientists, she realized that she needed international experience, so she traveled to the U.S. to complete postdoctoral studies at Cornell University and University of California-Davis. Her experience in the U.S. provided her with the scientific training to develop international projects and contacts with laboratories in other countries, allowing her to advance in cutting-edge research.

Though she received offers to stay in the U.S., Hungria always intended to return to Brazil because she knew there was so much more that could be done there with soil microorganisms to support sustainable food production. Instead of returning to the Embrapa Center for Agrobiology, she transferred to Embrapa’s National Soybean Center in Londrina, where she had better access to medical care and education for her children and could live closer to her grandparents. Though this meant that she would have to build a new laboratory and start her research from scratch, she was more than ready for the challenge.

Hungria’s brilliant scientific work, commitment to sustainable crop production and microbiological innovations have gained her global recognition as a transformative agricultural development scientist both at home and abroad. She has been invited to head project committees on almost every continent. She was the only microbiologist on the steering committee for the 10 years of the Gates Foundation-funded N2Africa project. She received the TWAS-Lenovo Science Award and was named a Commander of the National Order of Scientific Merit by President Lula. She was also inducted into the Brazilian Academy of Sciences and the The World Academy of Sciences, and was elected the first woman president of the Brazilian Society of Soil Science. She has written over 380 scientific articles and was listed among the 100,000 most influential researchers in the world by Stanford University.

Hungria’s brilliant scientific work, commitment to sustainable crop production and microbiological innovations have gained her global recognition as a transformative agricultural development scientist both at home and abroad. She has been invited to head project committees on almost every continent. She was the only microbiologist on the steering committee for the 10 years of the Gates Foundation-funded N2Africa project. She received the TWAS-Lenovo Science Award and was named a Commander of the National Order of Scientific Merit by President Lula. She was also inducted into the Brazilian Academy of Sciences and the The World Academy of Sciences, and was elected the first woman president of the Brazilian Society of Soil Science. She has written over 380 scientific articles and was listed among the 100,000 most influential researchers in the world by Stanford University.

She has been a staunch advocate and mentor for women scientists, lifting up other women in agriculture. As a professor at the State University of Londrina, she supervised more than 200 students, most of them women, guiding them in their professional careers in agricultural science. With authenticity and compassion, she shares her dual journey as a scientist and mother to encourage others who face similar difficulties to thrive in the complexities of both roles and has become an advocate for parents of children with special needs at Embrapa.

“It was a surprise—by sharing my experience of being a young mother, a mother of a child with special needs, and succeeding in science, I began receiving dozens of emails and messages from women saying that they now felt confident to move forward,” Hungria said. “I have found that by sharing my story, I inspire and give confidence to women (and men) to keep going, even in the face of challenges. My family strengthens me and my work strengthens my love and care for my family. To live, to breathe, I need both—family and science.”

In a time of immense pressure to produce more food with less resources and lower environmental impact, Hungria’s work on the use of microorganisms towards achieving regenerative agriculture uplifts and reinforces sustainable production, eco-innovation, re-carbonization, One Health, and above all, food security.

Additional Links

Mariangela Hungria is a co-winner of the 2020 TWAS-Lenovo Science Award

Forbes List of 100 Most Powerful Women in Agriculture in Brazil

Interview with Prof. Mariangela Hungria, Senior Researcher, Embrapa, Brazil

Prêmio Fundação Bunge 2022: Mariangela Hungria da Cunha

Inoculação Multifuncional para pastagens: processo de desenvolvimento

“Sua vida acabou”, ouviu a mulher que faz o agro economizar US$ 40 bi