Simon N. Groot

THE NETHERLANDS

Simon N. Groot of the Netherlands received the 2019 World Food Prize for his transformative role in empowering millions of smallholder farmers in more than 60 countries to earn greater incomes through enhanced vegetable production, benefiting hundreds of millions of consumers with greater access to nutritious vegetables for healthy diets.

Full Biography

When Groot started East-West Seed, commercial vegetable breeding was all but unknown in the tropics. Smallholder farmers struggled to grow a good crop with low-quality, poorly adapted seed that they often saved from season to season. Low-quality seed resulted in low yields, which translated into poverty and malnutrition for farmers and their families. Groot sympathized with the farmers’ plight, and saw a way to break the vicious cycle of poverty and help farmers achieve prosperity through diversification into high value vegetable crops.

After years of dedicated research and development, starting in the Philippines with business partner Benito Domingo, Groot introduced the first locally developed commercial vegetable hybrids in tropical Asia. These varieties were fast-growing, high-yielding and resistant to local diseases and stresses. Groot also realized that in order for farmers to maximize the value of these high quality seeds, they needed training on improved vegetable cultivation. Working closely with local and international NGOs, Groot created East-West Seed’s innovative Knowledge Transfer program--a unique feature for a seed company--which trains tens of thousands of farmers each year in good agricultural practices for vegetable production. As a result of better seeds and farming methods, farmers saw a dramatic increase in their profits, doubling or even tripling their incomes, and consumers found greater availability of these nutritious vegetables in their local markets.

Today East-West Seed serves over 20 million smallholder farmers in more than 60 tropical countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America. Groot has led the transition of millions of subsistence farmers, many of them women, to horticulture entrepreneurs, thereby greatly enhancing their livelihoods and income. These farmers have invigorated both rural and urban markets for vegetable crops in their communities, making nutritious vegetables more widely available and affordable for millions of families each year.

Groot has truly shown the world what can be achieved when agricultural industry places the needs of smallholder farmers at the heart of their business. In his own words: “That’s my number one passion: better seeds for small farmers.”

A Sixth-Generation Seedsman

“I think I was born to be a vegetable seedsman.” ~ Simon N. Groot

Simon Nanne Groot was born in 1934 in Enkhuizen, a small Dutch town known for its world-class seed companies. Enkhuizen gained this distinction in no small part due to the activities of Groot’s own ancestors, who had been in the seed business for five generations. His great-great-great grandfather Nanne J. Groot entered the seed business at the start of the 19th century, pioneering Holland’s top-notch seed industry. Decades later in 1867, Simon’s great-grandfather combined forces with another family member and founded the seed company Sluis & Groot, the management of which was passed to their descendents, including Simon’s father Rutger Jan Groot.

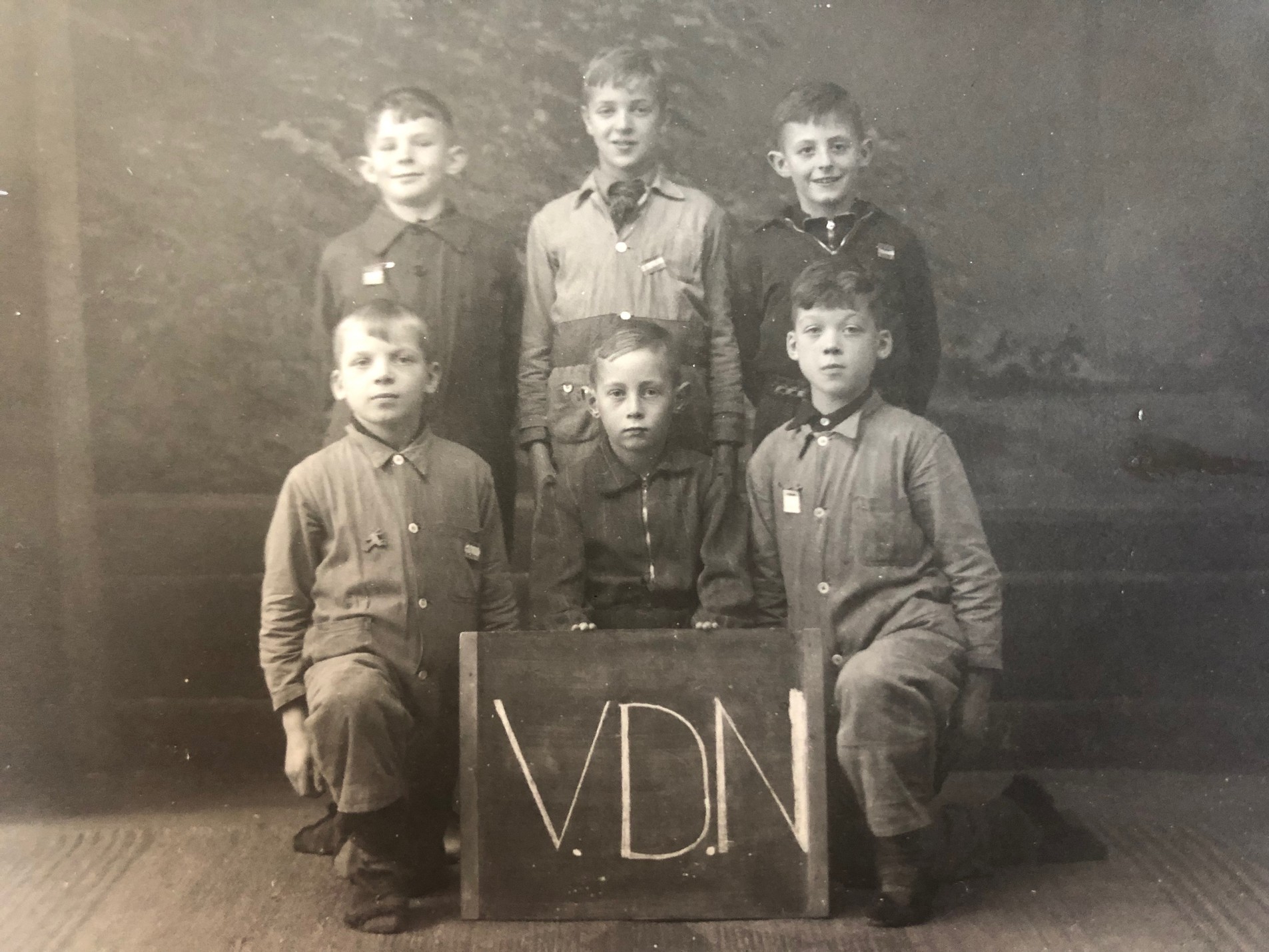

As a boy, Groot enjoyed reading and scouting with the local “Friends of Nature” boy scout club. Exploring the natural world was a passion that would remain near to his heart throughout his life.

As a boy, Groot enjoyed reading and scouting with the local “Friends of Nature” boy scout club. Exploring the natural world was a passion that would remain near to his heart throughout his life.

One of his earliest impressions of the value of seeds came in World War II, during the German occupation of the Netherlands. The Germans were well aware of the importance of Enkhuizen for their seed supplies, and as a result the small town received far more lenient treatment than other areas of the country such as Arnhem, where Groot’s future wife Koen lived. Through close contacts with farmers throughout Holland, Enkhuizen also managed to avoid the famines that struck other urban areas. Seeds were what saved Groot’s hometown.

After graduating from Erasmus University Rotterdam with a degree in business economics and serving two years as an officer in the Royal Dutch Army, Groot entered the family business in 1958 at his father’s urging. One of his first assignments upon starting at Sluis & Groot was a training ship with Chicago-based Vaughan’s Seed Company, where he would learn more about the U.S. seed industry and practice his English. After crossing the Atlantic by ship and half the North American continent by train, Groot found himself in Winfield, Illinois, where the seed industry was in the middle of a transition from traditional methods to more sophisticated plant breeding programs.

“That was a fascinating development,” Simon recalled. “You could see how it was modernizing and how the seed quality was going to play a much bigger role in the life of the farmers, and moving away from farmer-saved seeds for many crops into professional seeds produced by professional seed people and backed up by science. That was an exciting period in the industry.”

Groot’s eye-opening sojourn in the U.S. showed him several opportunities to start innovating parts of the industry in Holland when he returned home to Enkhuizen. Throughout his subsequent travels to the U.S. and many other countries as a seed salesman, he kept his eyes open for other opportunities to innovate. He eventually rose to the position of Marketing Manager at Sluis & Groot, leading the company’s hybrid flower seed breeding programs to the global forefront of the industry.

In 1965, Groot went on his first business trip to Indonesia to arrange flower seed production for Sluis & Groot. There in the highlands above Jakarta, he discovered a field planted with cabbages of the variety “Glory of Enkhuizen,” a variety that his own company bred and distributed. Though this variety grew well and uniformly throughout Europe, in Indonesia it was producing fewer heads, many of them misshapen. The variety which had been bred to thrive in a temperate climate had fizzled in the tropics.

In 1965, Groot went on his first business trip to Indonesia to arrange flower seed production for Sluis & Groot. There in the highlands above Jakarta, he discovered a field planted with cabbages of the variety “Glory of Enkhuizen,” a variety that his own company bred and distributed. Though this variety grew well and uniformly throughout Europe, in Indonesia it was producing fewer heads, many of them misshapen. The variety which had been bred to thrive in a temperate climate had fizzled in the tropics.

“The thought struck me that here was a huge opportunity--to introduce hybrid cabbage to the tropics,” Groot recalled. This idea would stick with him for sixteen years until he would finally find himself in a position to do something about it--and transform the lives of millions of farmers in the process.

In 1981, Sluis & Groot was sold to Swiss company Sandoz, later becoming part of Syngenta. Ready for a new venture, Groot left his position as Marketing Manager and set out on a mission to bring the technological innovation that he had been a part of in the ‘60s and ‘70s in Holland’s seed industry to the tropics. Following in the footsteps of his great-great-great grandfather, he headed off to pioneer localized vegetable breeding and seed production in Southeast Asia.

East Meets West

For the first 20 years of his career at Sluis & Groot, Simon Groot was always on the lookout for new opportunities in the seed industry. At the age of 47, he embarked on an exploratory tour of Southeast Asia, digging into the details of the seed industry in the region, talking with seed tradesmen and farmers, and visiting vegetable markets. He was looking into the feasibility of the vision he had in mind--to set up the region’s first vegetable seed breeding company.

This was far more easily said than done. The market for improved, high-quality vegetable seeds did not exist in Southeast Asia at that time. When vegetable seed was available, it was often from expired lots coming out of Europe and North America, and this low quality seed was poorly adapted to tropical growing conditions. Many smallholder farmers saved their seed season to season rather than take the risk of purchasing poorly adapted, low quality seed. The result of this system was low vegetable yields, extremely variable produce quality and rampant plant diseases, which made the job of the farmer very difficult.

Groot’s sensibilities as a seedsman were inflamed by the poor quality seeds that Southeast Asian farmers had to get by with. He saw the potential for improved, high quality vegetable seed to make an enormous difference in the livelihoods of smallholder farmers. There was no established market and no commercial breeding activities currently taking place. He would have to start entirely from scratch with only his own limited capital, as there was no bank or other organization that would fund such a venture.

It was in the Philippines that he discovered just the partner to help bring his plans to fruition. Benito Domingo had the local connections to the traditional seed trade, agriculture industry and universities, as well as a passion for seeds. With Groot’s experience of more than 20 years in the seed and plant breeding industry in Europe and North America, the two made quite the complementary combination. They went into business together, and to show their partnership between an Asian and a European, they named the firm East-West Seed Company.

The First Hybrids

East-West Seed started small, with a five-hectare farm outside Lipa City, Batangas, to begin initial plant breeding activities and train local people as breeders and technicians. Rather than import seeds, Groot enlisted well-trained plant breeders from Wageningen Agricultural University in the Netherlands to jump-start the breeding process and help train locals. This association with Wageningen was among the first of the many public-private partnerships that Groot would cultivate through the years to aid his mission to bring quality seeds to smallholders.

It was four years before any seeds were ready to market, which meant four years of expenses to be paid with no revenues coming in. Investing the first few years so that the breeding program could have time to yield results was vitally important for the success of Groot’s endeavor. He wanted producing quality seeds adapted to local conditions to be the focus of the business from the beginning.

It was four years before any seeds were ready to market, which meant four years of expenses to be paid with no revenues coming in. Investing the first few years so that the breeding program could have time to yield results was vitally important for the success of Groot’s endeavor. He wanted producing quality seeds adapted to local conditions to be the focus of the business from the beginning.

Groot knew he had to build the business based on trust between the farmer and the seedsman. Any defect in seed quality will hurt the farmer’s income, so farmers will buy the seed of a new variety only after seeing its performance in their or a neighbor’s field. Therefore, Groot and his team paid close attention to farmers’ growing conditions and local consumer preferences to select desirable varietal traits. Groot also instituted a very rigid pre-commercial release screening system of new varieties to be absolutely sure that the product was truly effective for farmers and enhance the farmer’s income.

“It’s a very special type of business,” Groot said. “It’s details--and you have to have a passion for farmers and for agriculture and for the land. You have to have a high sense of quality because any quality defect causes damage to farmers’ income. You have to have a sense of science to use all these new technology options. So, my business was more about building people than creating seeds. It was getting the right people to do it.”

The first priority of East-West Seed’s breeding program was bitter gourd. Bitter gourd (Momordica charantia) is an amaroidal but nutritious Asian vegetable that is largely unknown in the west. Groot recognized that this high-input, high-price crop was ripe for hybrid development, as farmers who were already investing in trellising and other inputs would be more amenable to paying a good price for quality seeds.

At first, the breeding process was extremely difficult. Everyone on the research farm was in the process of learning--how to grow the crops, how to pollinate, how to make selections and many other details that are essential to plant breeding. The staff quickly learned their trade, and in early 1984 made a promising cross that was vigorous, high-yielding, large-fruited and tolerant to diseases like downy mildew. They named this new variety “Jade Star.”

Sample seeds of Jade Star were distributed to farmers in Cavite province, Southern Luzon, but the initial reaction of the farmers to the hybrid was discouraging. They did not even want to try the hybrid, as it was more labor intensive and required more fertilizer, and most farmers were not ready for new varieties or new technology.

Nevertheless, they managed to convince several farmers to plant trials. Most of the trials failed, as the farmers were not used to the new variety and did not handle it properly. There was one farmer, however, who managed to get good results from his trial. He was convinced of the value and advantages of the hybrid, and the next season he planted Jade Star again, this time in a much larger field. The high yield and excellent quality of his crop resulted in a huge return for the farmer. His neighbors took notice, and within three years many of the bitter gourd growers in Cavite were planting Jade Star.

Jade Star was the Philippines’ first hybrid vegetable variety, created in the Philippines for Filipino farmers and for Philippine growing conditions and markets. In fact, it was the first locally developed commercial vegetable hybrid in all of Southeast Asia. New varieties soon followed of other vegetables, including kangkong, yardlong bean, sweet corn, tropical pumpkin, ridge gourd, wax gourd, cucumber, tomato, watermelon, eggplant, onion and many more.

With the Philippine branch of East-West Seed well underway, Groot began to expand to Thailand. With new Thai partners in 1984, he established Thailand’s first commercial vegetable breeding farm in the Chiang Mai valley and got to work developing a Thai bitter gourd hybrid. Groot recognized right away that Philippine bitter gourd varieties could be crossed with Thai varieties to improve plant vigor and disease tolerance. This insight soon resulted in the first Thai commercial vegetable hybrid “Sae Yid,” which became a runaway success, covering 20 percent of bitter gourd plantings in Thailand in just the first four years.

With the Philippine branch of East-West Seed well underway, Groot began to expand to Thailand. With new Thai partners in 1984, he established Thailand’s first commercial vegetable breeding farm in the Chiang Mai valley and got to work developing a Thai bitter gourd hybrid. Groot recognized right away that Philippine bitter gourd varieties could be crossed with Thai varieties to improve plant vigor and disease tolerance. This insight soon resulted in the first Thai commercial vegetable hybrid “Sae Yid,” which became a runaway success, covering 20 percent of bitter gourd plantings in Thailand in just the first four years.

Groot’s fanatic attention to detail in adapting vegetable varieties to local conditions was an essential part of reaching as many smallholder farmers as possible. No niche market was too small for him to take notice. He introduced small, inexpensive packages of high-quality seeds that were tailored for smallholders to plant small plots of land. Then when he expanded East-West Seed to Indonesia in 1990, he established three breeding farms to research highland, lowland and mid-altitude crops. This strategy produced varieties adapted to each area, including Indonesia’s first successful commercial lowland tomato. Now lowland farmers could produce tomatoes for nearby markets, and there was no longer a need to truck in highland tomatoes.

In the 1990s, other companies in Southeast Asia began to follow Groot’s lead in developing hybrid vegetable varieties. The now flourishing hybrid vegetable seed industry in Thailand and many other Southeast Asian countries owes its beginning to Groot’s persistence in paving the way in the market and proving to others the potential in hybrids.

Knowledge Transfer

As hybrid vegetable varieties gained in popularity among Southeast Asian smallholder farmers, the development potential of vegetable production soon became apparent. Vegetable farming was frequently more profitable than other types of agriculture because of the more intensive land use, the ability to grow vegetables year-round, and the high economic value of vegetables. Using East-West’s seeds multiplied this increase in farmers’ income both by yielding more and growing higher quality produce that commanded a premium market price. For every additional dollar spent on high-quality seed, farmers experienced a return on investment of at least five dollars and often more, even up to 50 dollars.

However, it also became clear to Groot that not every farmer knew what to do to unlock the potential and maximize the benefits of these new seeds. Many farmers still used traditional farming methods that were not optimal for insect control, watering, and soil nutrients and conservation. In the Philippines for example, farmers were hesitant to grow any crop except rice during the rainy season because they believed other crops would fail due to the heavy rains. Groot, though, had discovered that with proper drainage it was possible to grow excellent vegetable crops during the rainy season, which were far more profitable than rice.

However, it also became clear to Groot that not every farmer knew what to do to unlock the potential and maximize the benefits of these new seeds. Many farmers still used traditional farming methods that were not optimal for insect control, watering, and soil nutrients and conservation. In the Philippines for example, farmers were hesitant to grow any crop except rice during the rainy season because they believed other crops would fail due to the heavy rains. Groot, though, had discovered that with proper drainage it was possible to grow excellent vegetable crops during the rainy season, which were far more profitable than rice.

This and others were lessons that Groot wished to pass on to the farmers. He set up field training programs and demonstrations in selected areas that trained farmers on improved agricultural practices. These farmers became demonstration farmers that helped train their neighbors in turn on what they had learned. This gave farmers practical skills and introduced them to new technologies that would help them improve their profitability.

These trainings grew to become East-West Seed’s Knowledge Transfer program--the first time a seed company had invested heavily in capacity building for its customers. Through partnering with other international and local organizations, Groot expanded the Knowledge Transfer program quickly. Now 100 staff train more than 56,000 farmers each year in eight countries in Asia and Africa, and aim to reach millions more through other media, such as crop guides translated into the local languages and instructions that are accessible to all education levels.

Spreading Success

“Seeing big smiles on faces of farmers has given me tremendous satisfaction as I can observe from these smiles that what we have done for them is really of value and meaning.”

As Groot predicted, quality seeds were the starting point for a cascade of value creation. Farmers planting hybrid seeds got higher yields and better quality produce that sold for higher prices. These high-quality, attractive vegetables induced consumers to buy more of them. Innovative farmers with the help of the Knowledge Transfer program quickly adapted their farming systems to optimize their production. They adopted technologies and techniques such as drip irrigation, fertigation, plastic mulch, pruning, seedling trays and stronger trellising to increase their yield and quality and extend their growing season. The diversity of hardy, nutritious vegetable crops with shorter growing cycles and use of efficient irrigation also reduced farmers’ vulnerability to climate change and market shocks. The increased production resulted in greater accessibility and affordability of vegetables in rural and urban markets.

With the high-energy, hands-on approach exemplified by its founder, East-West Seed has taken on the challenge of expanding the vegetable sector throughout Southeast Asia, with an emphasis on training farmers in vegetable production. The work of Groot and East-West Seed has led to a long line of beneficial developments in markets, farming operations and rural revenue streams, resulting in huge economic impact that could not have been produced by public aid programs alone.

With the high-energy, hands-on approach exemplified by its founder, East-West Seed has taken on the challenge of expanding the vegetable sector throughout Southeast Asia, with an emphasis on training farmers in vegetable production. The work of Groot and East-West Seed has led to a long line of beneficial developments in markets, farming operations and rural revenue streams, resulting in huge economic impact that could not have been produced by public aid programs alone.

“The development role of the seed business has been underestimated,” Groot said. “Reliable seed is the first tool that must be available before any other development can proceed. And who can provide that seed except seed companies who get their revenues from the market and then plow those funds back into the breeding effort in a structured, market-oriented way?”

Over the last four decades, Groot has expanded East-West Seed across Asia, into Africa and now into Central America as well, all the while keeping smallholder farmers’ interests at the center of the business. The Access to Seeds Index ranks East-West Seed first among vegetable crop seed companies on its efforts to make quality seeds accessible to smallholders. In 2017, East-West Seed sold 24 million value packs for $1 each, which contain a small amount of high-quality seed that is perfect for smallholders to plant small plots with vegetables.

Over the last four decades, Groot has expanded East-West Seed across Asia, into Africa and now into Central America as well, all the while keeping smallholder farmers’ interests at the center of the business. The Access to Seeds Index ranks East-West Seed first among vegetable crop seed companies on its efforts to make quality seeds accessible to smallholders. In 2017, East-West Seed sold 24 million value packs for $1 each, which contain a small amount of high-quality seed that is perfect for smallholders to plant small plots with vegetables.

More than 20 million farmers in 60 countries plant East-West Seed’s 973 improved varieties of 60 vegetable crops on 28 million hectares. With these seeds and techniques learned from Knowledge Transfer, farmers have doubled or tripled their yield and more than doubled their incomes. Their high quality, nutritious vegetables reach hundreds of millions of consumers, especially women feeding their families, at an affordable price. The red arrow of East-West Seed’s logo is a household name among Southeast Asian farmers.

Groot has been a source of inspiration to many, including other seedsmen and companies that followed his example in entering the vegetable breeding industry in underserved regions of the world. He was a founding father and still an active member of the Asia and Pacific Seed Association, as well as a consortium of vegetable breeders to support the World Vegetable Center (formerly AVRDC) with funds and expertise. Three of his four children have followed him into leadership positions in the business, ensuring that East-West Seed remains a family company and continues to adhere to their father’s vision and values. And yet, Groot would be the first to say that there is still more to do to reach farmers who need better seeds the most:

“You have to share your knowledge if you want to make the world better.”

Additional Links

2019 Laureate Luncheon Transcript

Groot: What the World Food Prize Means to Him

Groot - The Borlaug Blog: A Vegetable Revolution